Alan Dowds provides the insight…

The basic geometry of a bike’s chassis is vital to how it feels and performs. But it can seem like a bit of a black art sometimes. Here’s our guide to what it all means – plus the very latest in track bike set up thinking. What do you look at when you first see the specs for a new bike? If you’re anything like me then that’s a bit of a daft question – it’s all about the brake horsepower and the dry weight, isn’t it? Then we’ll maybe enquire about how fancy the brake calipers and suspension are. Finally, we’ll skim-read the electronic aids package – then all that remains is to see if it comes in colours to match a rainbow. The question is, do you ever look to the lower reaches of the chassis specification, though? The rake and trail figures, and the wheelbase? Those are the headline figures on a chassis layout, but there’s a host of other details which the engineers and test riders have been sweating over for years. Fork offset, wheel sizes, swingarm length, engine mount position, rear ride height, chain run, weight bias – all have subtle effects on how a bike chassis will work… or not work.

Grasping the fundamentals… Let’s start with the basics then – those figures we put in the specs. Rake is pretty simple: it’s the angle of the steering head, measured from an imaginary vertical line through the steering head. More rake means the front wheel is pushed farther out away from the engine, like a cruiser. Less rake means the wheel is pulled back, closer into the motor, like a Moto3 race bike. Trail is a little bit more complex. Here, we imagine a vertical line drawn down through the front wheel axle to the ground, and another line drawn through the steering head to the ground. The trail is the difference between where those two lines touch the deck. More trail means more stability and slower steering – so, again, our cruiser bike would have a higher trail figure than a supersporty machine. That ‘usually’ comes with more rake, but there are other factors which affect the trail figure.

Enjoy everything More Bikes by reading the MoreBikes monthly newspaper. Click here to subscribe, or Read FREE Online.

Fork offset: the distance between the steering head angle and the line of the forks. And then there’re wheel sizes and tyre profiles; they will all affect trail. Finally, wheelbase is simply the distance between the points where the front and rear tyres touch the ground. Sports bikes have a shorter wheelbase, touring and cruiser bikes have longer wheelbases. Drag racing bikes have wheelbases so long it takes at least two tape measures to identify the distance… or so I’m told. Okay, maybe a bit melodramatic, but when you consider the defining rule in classes like Super Street Bike sees drag bikes with a wheelbase of up to 1780mm, you get the point that they’re pretty damn lengthy. Back to the point. These three measurements we’ve just covered define much of what makes a bike more, or less, stable. That’s down to the self-centring or ‘castoring’ effect (hence ‘castor’ wheels on sofas and shopping trolleys).

The contact point of the front tyre is behind the steering axis, so when you turn the steering while moving forward, there’s a self-centring force created which tries to return the wheel back to the straight-ahead position again. You can check it next time you’re schlepping round Asda – stop the trolley, turn a wheel sideways, then watch it go straight the instant you push the trolley forward. The longer the distance between contact point and axis, the more leverage this self-centring force has, and the stronger the effect. In the ultimate case of a vertical steering axis, with zero rake and trail, there’s no self-centring force at all, and the steering would never return to the middle – zero stability in other words. At the other end of the scale, imagine the wackiest of wacky Bike EXIF concept cruisers with the forks arranged parallel to the ground – giving infinite trail and 90 degrees of rake. Now, the steering doesn’t change the direction of the front wheel at all – turning the bars would just tilt it from side to side, and you’d have zero steering effect, but you’d have infinite stability.

There’s a similar effect with a longer wheelbase – the further back the rear wheel contact patch is from the front tyre, the stronger the urge for the bike to keep moving in a straight line. A shorter wheelbase means the rear tyre has less self-centring effect, so you have more instability, and faster turning. Very stable layouts – lots of rake and trail and a long wheelbase are obviously useful when you’re hitting 200mph+ down the main straight at Mugello. But when you want to turn quickly through a chicane, then you want the bike to be less stable – so shorter wheelbases, less rake and shorter trail is the answer, right? Well, yes, and no. As ever with an engineering problem, there’s a compromise here. Shorter wheelbases make a bike more likely to wheelie under acceleration, and stoppie when braking. And the reduced stability means tank slappers and speed wobbles, too – so you have to add on a steering damper, which can slow the steering down again. Like air bubbles under a cheap iPhone screen protector, as you push some down, more pop up elsewhere.

Go back 20 years though, and you had to do exactly this – sharpening up the steering by lifting up the rear end and dropping the front of the bike. This effectively steepens the head angle, gives faster steering and means the rider can change direction faster. Getting leant over into a corner faster, and changing direction in a chicane would gain vital seconds, and on bikes like a Kawasaki ZX- 7R, Honda CBR600F, or Suzuki TL1000R, would make a big improvement in agility. In recent years, however, this has become less effective. Standard bike chassis are sharper than 15-20 years ago, and superbikes now come with superb agility as stock – so if you start to tip them on to their nose even more, you can make a right mess of the handling. They also now make nearly 200bhp without too much effort, so taking weight off the back end and putting it on to the front can mean there’s not enough grip under acceleration. So, for many racers nowadays, dropping the back end and lifting the front can actually give better handling. Having a slightly more relaxed geometry improves stability – A Good Thing with a 210bhp, 180kg track bike – and also gives better grip when on the gas. Those benefits can outweigh the downsides of increased wheelie-tendency, and slightly slower steering. Indeed, our very own fast guv’nor, Mr. Bruce Wilson, has discovered exactly this on his GSX-R1000 race bike. He’s lifted the front end by 24mm, by moving the forks in the yokes, and has transformed the handling as a result (…even though his lap times suggest otherwise). As with all chassis set up techniques though, there’s no ‘ideal’ prescription.

We’re not saying that you should go out and fit apehangers and extralong Multistrada forks to your Panigale V4 (though we’d love to see the pics and video if you do). Rather, the notion of adding stability to your geometry mix in this way is another option, which could improve the handling of a modern high-power superbike on track in certain circumstances. The basic geometry is only part of the story, of course; there are loads of other factors which go into the overall handling story. The bike’s centre of gravity affects stability – higher CoG is less stable, lower moreso. The length of a swingarm reduces the effect of high-powered engines on weight transfer. And now, cunning electronics can control wheelies off the gas and stoppies on the brakes – so you can make your chassis more ‘edgy’ and unstable, then smooth off the handling edges with an IMU-assisted stability package. Whatever your handling needs though, we hope you’ll pay more attention to those chassis specs on all the new bikes when they appear…

How to make your bike handle…

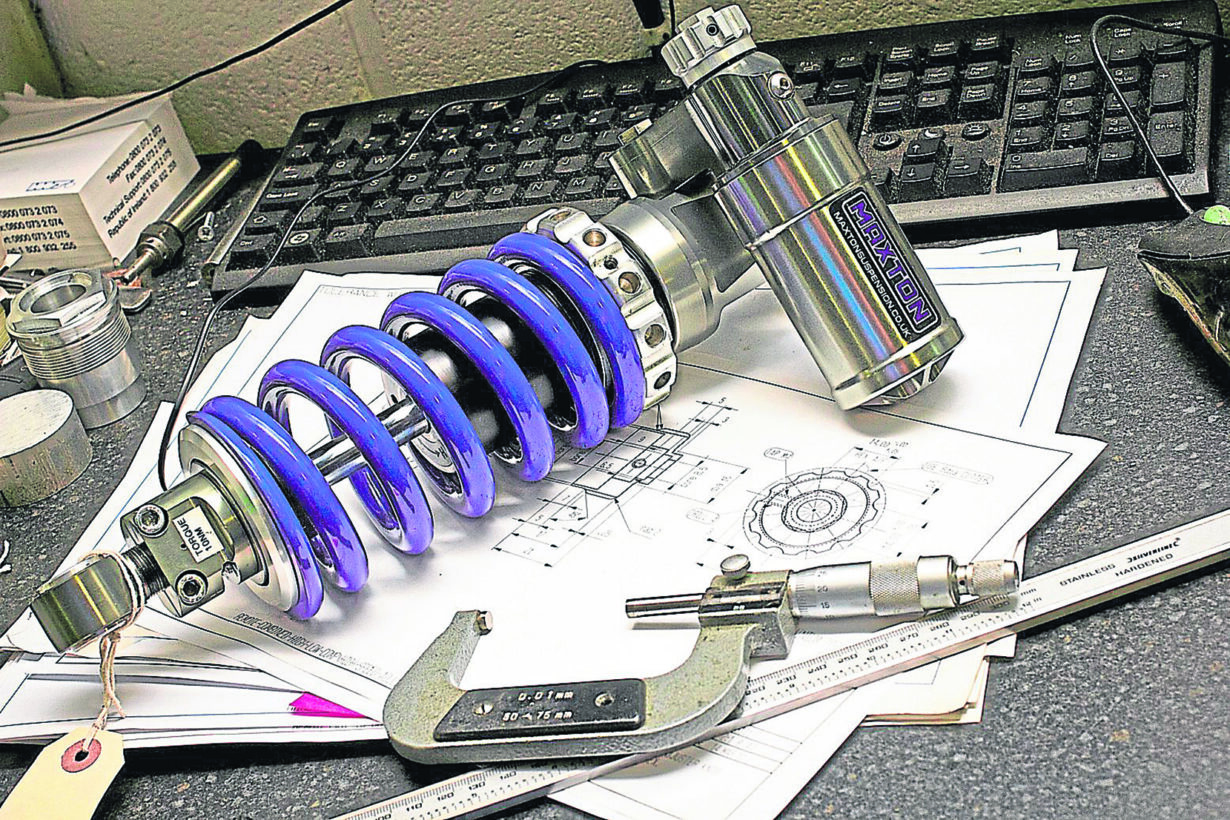

When it comes to altering the geometry and characteristics of your bike, there’s quite a bit that can be done. Of course, just how much adjusting you do exaggerates the differences you’ll experience, but here’s a rough guide to what you could change to make your bike ride differently:

Faster steering There are a couple of ways to make a bike steer faster, but perhaps the simplest way to alter the speed at which your bike turns is to put more weight over the front of it. If you were to lower the nose of your bike, via preload or by dropping the forks through the yokes, you would be increasing the weight bias of the bike towards the front, and consequentially altering the ride height. At the same time, you’d also be shortening the wheelbase of the bike, which is a proven way to increase the nimbleness of your package.

Of course, the simplest way to do so, without upsetting your ride height, is to shorten your wheelbase by changing your gearing.

More stability If you’re struggling with stability on a straight or through a corner, you can try a couple of changes. By lengthening the wheelbase, you will reduce the bike’s susceptibility to become unstable. Quite often nervous motorcyclists have either very short wheelbases or have a lot of pressure over the front wheel. If you were to lengthen the wheelbase or raise the nose of the bike, on preload or via the lifting the height of the yokes, you should find your motorcycle is more stable.

More rear grip It goes without saying that if you’re weight bias is too far towards the front of your bike, there’s not enough weight or pressure on the rear tyre to cope with the power going through your rear wheel – especially on big litre sportsbikes. You can counter this by increasing the preload at the front of the bike – sending more weight to the rear – or by lowering the rear. The only problem with lowering the rear is that you can compromise ground clearance and alter the damping characteristics of the rear shock if you reduce the height too much.

How do brands build the best chassis?

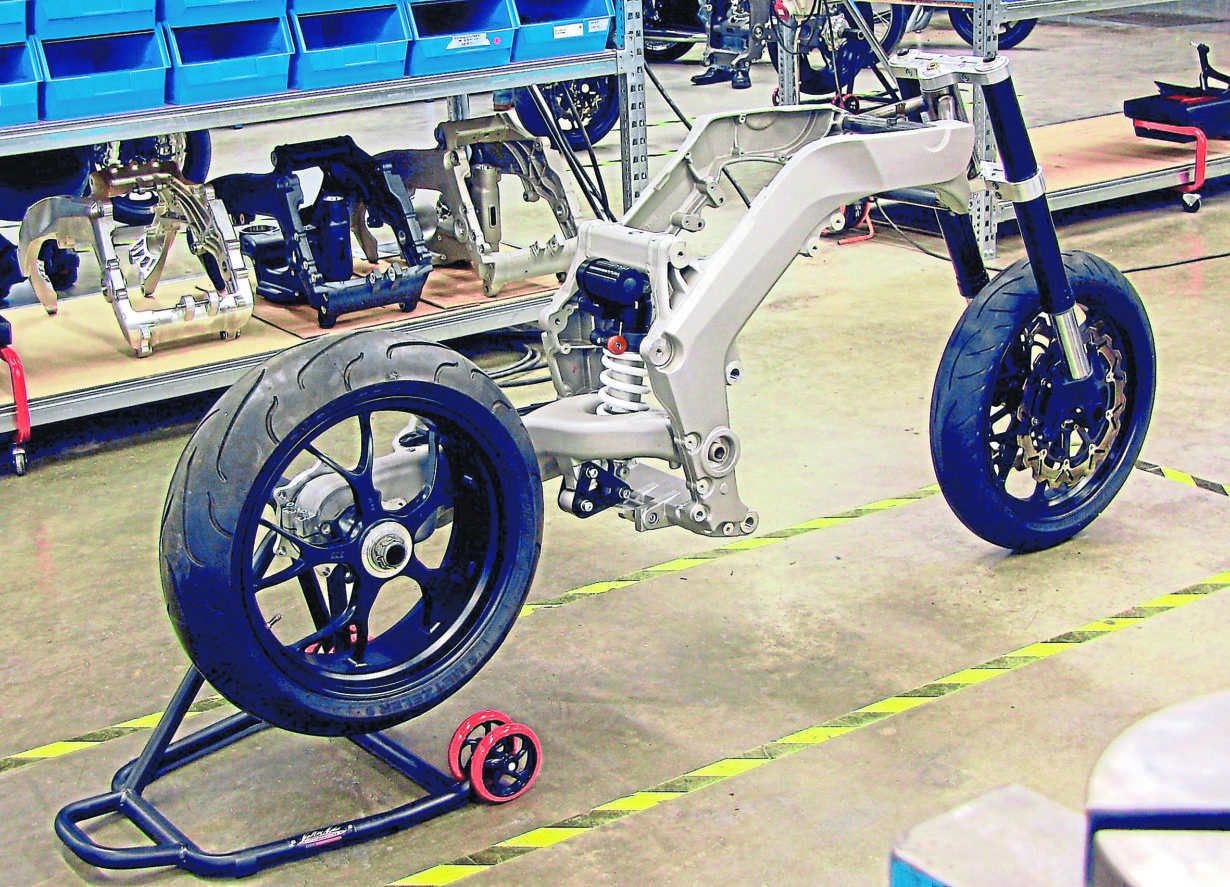

Cristian Barelli is Aprilia’s senior product marketing specialist, and he spoke to us about the RSV4 1100 Factory. While this isn’t an all-new bike for 2025, it is a model well known for its class-leading cornering credentials, and the only production superbike with a fully adjustable chassis: the steering head, swingarm pivot and engine mount points can all be fettled for the ultimate set up. We asked him:

Do Aprilia engineers have a geometry in mind when they start a design? “Before starting a new design, there is a stage of analysis of the existing motorcycles from Aprilia and the best competitors on the market. We are not self-referential and we try to approach any problem and design target without prejudice. So, we pick the reference bikes from the market, we test them using our evaluation grids, and we try to establish a good correlation between road or track behaviour and the most important measurable physical dimensions for a selection of bikes, not for one only.”

Are there ‘good’ geometry figures which you can start with? Has that changed over the years? “Unfortunately, it is more complicated than this: the steering geometry dimensions do not stand alone. They shall match mass and stiffness distribution and finally also forces and torques exchanged with the road and with the power unit as well. Of course, we try our best to define a ‘first tentative’ set of geometrical dimensions, but due to the high number of independent variables involved we do not know deterministic methods to define it, nor cannot evaluate how much stable this set of values will be during the development.”

Do you use ‘development’ frames at the early stages of design, with adjustability, or do you make different frames with different geometry to test? “In the first prototype for test, in the early stage of design, we tend to introduce as much adjustment as possible, but this often has the side effect of introducing clearances and/or differences in weight and stiffness that might be misleading. So, when possible, it is better to have a set of prepared parts with different geometry.”

With the RSV4’s adjustable frame, how would you recommend an owner experiments with the adjustments? “We believe the setting of the RSV4 frame, as it is downloaded from the assembly line, is the best compromise for that configuration of motorcycle ridden by a rider of average size. If a customer has a very personal riding style, or he wants to use the motorcycle on the track and he’s able to make it lighter and/or more powerful, then he can subsequently alter the chassis in order to meet the new mass distribution. In this case the elements of adjustments available from our accessories catalogue can allow the achievement of a new balance according to the new mass and power levels. “Unfortunately, so many variables can affect the final performance of the motorcycle dynamics (including wheels and tyres, electronics, aerodynamics, suspension setting, riding position, power level, rider attitude, etc.) so that in the past we have seen some modifications executed according to the most commonsense ‘rules of thumb’, giving back responses not exactly as expected even if managed by professional teams. Any different set up of the motorcycle has a story apart, and general simple rules can hardly find application.

Is the final steering geometry totally down to what the test riders feel is best? “Yes, taking into account that the final set up, according to Superbike Regulation, should be the same homologated and registered for SBK World Championship. For this reason it was approved and shared with our Racing Department. Anyway, we have developed our methods in order to procure some objective feedback (data logging and lap time) in order to make sure that any single modification, beyond the good feelings of our testers, allows an actual advantage in terms of performance target achievement.”